Announced as “the Olympics of AI”, France’s AI Action Summit, which just ended here in Paris, was supposed to find new meaning for artificial intelligence, notably defining a way for European AI to compete with US and Chinese domination of this still much-hyped sector. In short, it claimed to answer tech bros’ favourite question: how is [insert latest tech fad, in this case AI] making the world a better place?

Instead, it opened on February 10 with a flurry of funding announcements (expertly recapped here by Chris O’Brien). As if to reply to the US’ overblown $500bn investment in AI mega-project Stargate, president Emmanuel Macron announced a €109bn investment in AI in France in coming years. The UAE also said it would invest €30-50bn in the French economy, notably to build new datacenters, one with a capacity of 1 GW (enough to cover the needs of one GAFAM, for the record). And Mistral AI, France’s own OpenAI (of sorts), said it would open its own datacenter. In France, bien sûr !

In a nutshell, France’s self-styled “third way” looked mike throwing more money at AI, to make ever-more power-hungry models in ever-bigger and more numerous datacenters. Whilst leaning on the excuse that France’s electricity is particularly low in carbon (cue Macron’s Trump-sheeping “plug baby plug”, à la his “make this planet green again” quip not long ago… #cringe)

What about building AI models that don’t need as much energy as the current generative AI market dominators? Wouldn’t we need less power, and therefore less data centers, if we did that? Isn’t this what finding new meaning for AI is all about?

French Ministry leading sustainable AI efforts

That approach, which can be summarised as “Frugal AI”, is, after all, a French speciality, as Environment Minister Agnès Pannier-Runacher was keen to point out on day two of the Summit, at the “Sustainable AI Forum”, held at her ministry’s HQ, on February 11, as a welcome part of the AI Action Summit.

Indeed, not only did France’s AFNOR and Pannier-Runacher’s ministry came up with the “Frugal AI Framework” last year – the first of its kind to officialise what more resource-efficient AI could look like – but the same ministry demands that any AI providers looking to work with the French state declare their model’s emissions and impacts as a prerequisite (which rules out their working with the increasingly opaque OpenAI, for starters).

“AI’s environmental impacts are huge”, said Pannier-Runacher, opening the Sustainable AI Forum. “Training a LMM can use billions of litres of water… but none of this is set in stone,” she added, meaning this type of impact is not inevitable.

“Let’s make AI work for the planet, not against it”, she concluded, before calling onstage the members of the brand new Coalition for Sustainable AI (above), a grouping with an impressive member list, but less clear objectives, beyond working to reduce impacts across infrastructures, models and uses.

Glass half full?

To its credit, the Sustainable AI Forum gathered a stellar line-up of speakers, including some of the tech giants often held responsible for AI’s biggest impacts. But their “this is all under control” messages were in somewhat of a minority.

Google’s Global Director of Sustainability and Partnerships Antonia Gawel remphasised Google’s net zero 2030 commitment – a much-needed precision considering her company’s admission last summer that its emissions were going up, not down, due to AI. She then cited “AI for good” examples such as Google’s using AI to reduce planes’ chemtrails by 50% (chemtrails represent 1% of all global emissions, she said), or to predict floods up to a week in advance.

This was a welcome update to the old (2016) news that Google has used DeepMind AI to reduce data centre cooling bills by up to 40%. No mention was made, however, of how Google data centres consumed 6.1 billion US gallons of water in 2023, up 17% vs the previous year, or what it’s doing to reduce that amount.

Josh Parker, Head of Sustainability at GPU giant NVIDIA, was equally bullish. “The data suggests AI has a net positive effect. Over the past 10 years, the power needed for inference has been reduced 100,000 times. The performance per watt keeps going up.”

Parker also added that “water is becoming less of an issue very quickly.” NVIDIA’s next-generation Blackwell GPUs will bring a “300x improvement in water efficiency”, he said, as well as needing “96% less energy” [than previous generation GPUs].

So is everything fine, then? “Efficiency (alone) is not going to solve the problem”, admitted Parker, “because of increased demand. We still think AI’s energy consumption is only 1% of the global total. And it can reduce energy consumption, for example in manufacturing, by up to 30%. So the knock-on energy impacts [of AI] are considerable…”

Glass half empty

The ‘30% energy gains in manufacturing’ claim was questioned by David Rolnick, Co-Founder of Climate Change AI, a speaker in a subsequent panel. “That’s not generative AI [driving energy efficiency gains]”, said Rolnick. “We’ve made a model with 100 parameters which is beating the big models at their own game, because they’re made for a specific purpose, such as agriculture. We need smaller, smarter AI; not bigger, broader AI. We need the right tool for the right job.”

This call was echoed by Hugging Face’s AI & Climate Lead Sasha Luccioni (somewhat naturally given her (et al’s) “Bigger-is-Better” white paper): even if we do need to keep building ever-bigger models, we can do so in a less impactful way. “Instead of building more data centres, we need to rethink the way we make models, about distributed compute,” she said. “You can train a model between New York and London, and not spend millions of litres of water cooling it. We need to rethink our assumptions.”

(Interestingly, that comment echoed NVIDIA’s Bryan Catanzaro a few months ago: “We’re going to find that instead of putting a million GPUs in a single data centre, we’re going to run training and inference in a more distributed way, so we can have better access to electricity, and scale in a more efficient way,” he said at ai-PULSE, in November 2024).

Recapping the impacts

It was also clear at yesterday’s event that way more transparency is needed before we can ever declare AI an net positive for the planet.

> First and foremost, with regards its energy impact. Whilst a number of reports, notably that prepared by Berkley for the US government, concurred late 2024 that energy consumption of US data centres is set to double, or even triple, before the end of the decade, a new study by Beyond Fossil Fuels confirmed a similar trend is set to become a reality over here (cf. all those new data centres mentioned above): in Europe, data centre electricity consumption is set to increase 160%, 2022-2030.

Sarah Myers West, Co-Executive Director of the AI Now Institute, referred to this report in her hard-hitting introduction to the Sustainable AI Forum, adding that such a rise in energy consumption could wipe out Germany’s planned emissions savings alone. “There is no version of the current AI boom that will lead to a sustainable future,” warned Myers West, adding that “AI is used to find more fossil fuels at a time when we should be using less” (more on that here).

Tim Gould, Chief Energy Economist at the IEA, added shortly afterwards that renewables cannot keep up: “renewable energy production has increased fivefold since 2010”, he said, “but demand has increased 8.5x, and that gap is being met by fossil fuels.” Whence the fear that the AI boom could slow down, rather than accelerate, the renewable energy transition…

> Secondly, with regards AI’s water impact. 45% of hyperscale data centres are in areas with high water risk, said Julie McCarthy of Nature Finance as a question to panellists, citing this report. No answer was given as to how to reduce this risk, despite the fact that, with new data centres set to pop up worldwide like mushrooms, their water consumption is expected to double, or even quadruple, by the end of the decade, again re. Berkley (tip: using less water-intensive cooling systems than the currently-preferred cooling towers would be a good start).

> Thirdly, hardware impact. Ask any expert – e.g. French Green IT pioneer Frédéric Bordage – and they’ll tell you the impact of hardware far outweighs any others (including emissions, which only account for 11% of total IT impacts). Ergo, the only way to understand and mitigate the true impact of (generative) AI is by accessing detailed life cycle analysis (LCA) data of tech products… which their manufacturers invariably do not provide. Anne-Laure Ligozat, IT professor at ENSIIE & LISN, was one of several Forum speakers to point this out. Fingers crossed NVIDIA and other major AI hardware players will hear this call soon. Meanwhile, associations like Boavizta will have to keep dissecting and destroying GPUs to come up with their own LCAs…

> Last but by no means least, the indirect impacts. As identified in Luccioni’s last white paper, there are three types of indirect, or rebound effects: material, economic and societal. As she explained in her Forum keynote, some are positive, like the fact that AI-enabled navigation apps like Google Maps have been shown to reduce emissions by an average of 3.4% by optimising journeys; some are negative, like the fact that one third of Amazon’s revenues are driven by AI recommendations. The fact remains that no assessment of AI’s impacts can limit itself to direct ones. “We need to look beyond environmental to economic and social impacts too,” said Luccioni; “otherwise our exchanges are too siloed.”

Looking ahead… to truly concrete solutions

In case it’s not clear yet, one major consensus of the Forum is that AI’s impacts – or at least grey areas – far outweigh its benefits for now. Which is why two specific initiatives showcased yesterday were more than welcome: AI Energy Score, and the Frugal AI Challenge.

The latter, organised by Hugging Face, NGO Data for Good and the French Ecology Ministry, asked developers to complete specific AI tasks across three key categories – text, image and audio analysis – and to do so whilst using as little energy as possible. The winning submissions, one per category, managed to use five to 60 times less energy than they would have done if they used generative AI. Bravo! Though of course, none of these feats are magic fixes. As Data for Good Co-President Theo Alves Da Costa pointed out, “there’s no frugality that stops AI recommending climatosceptical books on Amazon…”

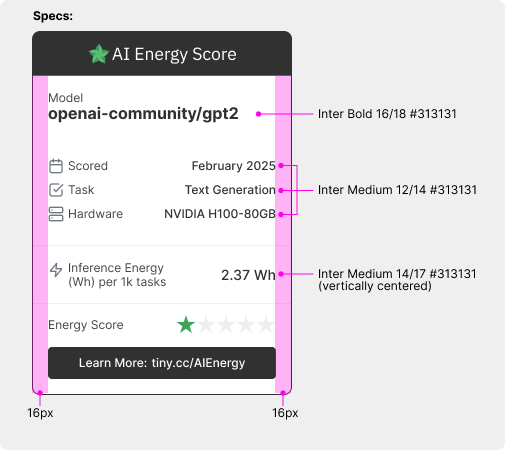

The former, developed by Luccioni and Salesforce’s Boris Gamayzchikov, Head of AI Sustainability at Salesforce, is designed to rank both open and closed models based on the amount of energy they use per request. As the project’s documentation puts it, “the primary metric for evaluation is GPU energy consumption, measured in watt-hours per 1,000 queries. By isolating GPU energy consumption, we provide an “apples-to-apples” comparison between models, focusing on efficiency under equivalent conditions.”

This allows for the creation of “Energy Star”-type labels (above), which can be associated with models as as if they were stuck on a fridge in a store 🙂

As Gamayzchikov told me, the process should be easy for makers of (transparent) open source models to follow and implement, which should encourage closed model makers (hello, OpenAI) to follow suit. And as a nice final touch, it suggests using methodologies from Ecologits.ai and ADEME to extrapolate other impacts (hardware, water) from energy.

AI Energy Score should as such encourage clients to make more informed choices… and hopefully, choose less impactful models. Fingers crossed…